Directed by

Sue Brooks

127 minutes

Rated M

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

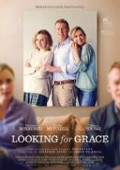

Looking For Grace

Synopsis: When rebellious Perth teenager Grace (Odessa Young) goes AWOL, her parents, Denise (Radha Mitchell) and Dan (Richard Roxburgh), enlist the help of Tom, a close-to-retirement detective (Terry Norris) and go in search of her.

Sue Brooks’ film has been widely criticized for its patchwork, nay even piecemeal, approach to its narrative which although having an easily identifiable beginning, middle and end, is told in non-linear. overlapping chapters. But is this really a fair criticism of the film itself or more a reflection of the reviewers’ frustration at a lack of a linear narrative with the sequential three act structure which is virtually synonymous with cinema as we know it? Couldn’t the film instead be offering us a refreshing approach to screen story-telling, one that takes advantage of the unique possibilities of film instead of subsuming it within the conventional form of time-honoured literary works? Although Brooks has no Godardian intent even this, insofar as it applies, has been peremptorily dismissed as a gimmick.

I would argue that there is a more meaningful reason for the non-sequential narrative structure of Looking for Grace and that is that Brooks is using the film’s form, just as much as its content, to bear her meaning, which is roughly speaking, that despite all our attempts at imposing order on the randomness of life with our institutions of marriage and family with their moral obligations and prescribed roles, the non-conformable, even anti-social, urges to which we are all prey are forever destroying the sought-for status quo. The film is saying, even more fundamentally, despite the ties that bind us we remain contiguous to each other, forever alone in our separate worlds, and it is from this solitude we are all seeking grace. In this respect, even though there is a superficial resemblance to films like Paul Haggis’s Crash (2004) Brooks’ purpose is not to bind together different story strands into a single overarching whole but, quite the reverse, to show the illusion of that whole, an illusion which narrative cinema has been perpetuating and reinforcing for over a century.

This philosophical position is a very Antipodean perspective, reflecting the wide, open spaces of our land, spaces that feature prominently in Katie Milwright’s fine cinematography and are manifested in the laconic, tentative dialogue that emphasizes the distance between characters rather than their closeness, particularly in case of Denise and Dan. In this respect the “stories” into which the film is divided are less neatly contained plotting strategies than fragments that serve to indicate an unseen reality that we must divine for ourselves (the otherwise unmotivated abstracted painterly imagery of the West Australian landscape with which the film begins sets us up for this). In this sense they answer to the Australian open-ended vernacular query “what’s your story?”, rather than being discrete components locking together in narrative form.

Certain artistic analogies come to mind in reflecting on Brooks’ approach, all of them traditionally associated with the minor arts, thereby and often with women practitioners. Mosaic-making and quilting could serve the purpose but perhaps the strongest analogy is with folk art or early Renaissance painting in which sequential time periods are shown within a unified representational form, say for instance the Crucifixion with Christ being betrayed in Golgotha, dying on the cross and being taken down by his disciples, all shown in two dimensional form but with shifting planes and perspectives.

Want something different?