Directed by

Cate Shortland

116 minutes

Rated MA

Reviewed by

Chris Thompson

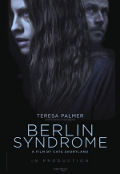

Berlin Syndrome

Synopsis: While holidaying alone in Berlin, Queensland backpacker, Clare (Teresa Palmer), meets German boy, Andi (Max Riemelt), a charming teacher of English while they wait at a pedestrian crossing. Before too long, they’re back at Andi’s apartment where Clare spends the night. When she wakes in the morning, Andi’s already left for work but she soon discovers that she’s locked in the apartment. An oversight on his part? That’s what he tells her when he returns at night, assuring her that he left a key for her then realising, apologetically, that it’s still in his pocket. But when Clare tries to use her phone she discovers the sim card has been removed and when tries to leave, things become ugly and she realises that she’s his prisoner in this seemingly empty apartment building with reinforced, soundproof windows and deadlocks on the door..Teresa Palmer really should give a bit more thought to kind of blokes she attracts. It’s only four years ago that she ended up as the main squeeze for a cute boy who, unfortunately, was a zombie in Warm Bodies. Now she’s (involuntarily) shacked up with a seemingly nice German boy who shares more than a few character traits with Terence Stamp’s Freddie Clegg character in William Wyler’s The Collector (1965). But in many ways, Cate Shortland’s third film (following on from her excellent 2004 debut Somersault and 2012’s WWII drama, Lore) is more than just an abduction thriller; it’s an examination of power within relationships and the vulnerability of a young woman who starts out as a trusting soul but soon has to become something quite the opposite in order to survive.

Adapted from Melbourne author, Melanie Joosten’s novel of the same name, the screenplay by Shaun Grant (who wrote Jasper Jones also in current release) doesn’t have the dark and terrifying edge of his earlier work on Snowtown (2011) opting instead to delve more deeply into the psychology of both captor and captive. To achieve this, Shortland sacrifices some of the thriller tropes in order to create a more thoughtful and slow-paced atmosphere which, for most of the film, is a welcome change from the stock-standard abduction and torture porn fare that is often the hallmark of this kind of story.

The title’s obvious nod to the Stockholm Syndrome (that phenomenon where the hostage develops a trust or affection for the hostage taker) is central to this story but it’s ambiguous in the way it makes us question whether the strange, developing relationship between Clare and Andi is for real or just a ploy to string him along until she can escape. What’s more interesting is the relationship that Shortland allows the audience to develop with Andi. We are the ones who are free to move with him outside the apartment. We are the ones who see him with his students, his friendships with his colleagues, his relationship with his aging father. Whilst this doesn’t instil an affection for Andi (at least it didn’t for me) it does provoke a kind of sympathy and understanding which we then bring to the artificial domestic world he is creating with Clare.

What makes the movie work (apart from Germain McMicking’s beautiful, moody cinematography and Bryony Marks’ trademark mournful soundtrack) are the excellent performances from Palmer and Riemelt who manage the very fine balance between their internalised emotional worlds and the externalised reality of an artificially forced relationship under duress. What lets the film down is an overlong, overplayed middle section that drags at the point it should be ramping up toward its climax; and a climax that leans more towards the convenient elements of genre than it does to the kind of conclusion more deserving of this otherwise engrossing and unsettling movie.

Want more about this film?

Want something different?