Directed by

James Marsh

123 minutes

Rated M

Reviewed by

Sharon Hurst

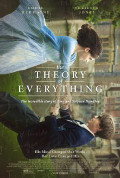

The Theory Of Everything

Synopsis: In 1963 young Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) is a smart and athletic physics student at Cambridge University. At a party he meets clever arts student Jane (Felicity Jones), and the pair fall in love. Then his world is shattered when he is diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease and given two years to live. Jane is determined that they should grasp whatever befalls them but when Stephen defies the odds and lives on for decades, their love must rise to the challenge.

Full credit goes to director James Marsh for taking such a challenging subject as Stephen Hawking and bringing us a film that is interesting, uplifting, sad and romantic all at the same time.

Anyone who has seen the actual Hawking knows what a trial his life is: confined to a wheelchair, with an electronic speaking device and virtually zero mobility, his remarkably piercing eyes staring from a distorted face and with a body no more than a twisted receptacle for a brilliant mind. Eddie Redmayne, a young fit fellow of course, manages to capture the sad trajectory of Hawking's cruel fate while maintaining the trademark twinkle in the eye. The young actor takes his body from the early clumsy stages of MND through to the absolute immobility that is now Hawking’s lot. It is an incredible (and Oscar-winning) performance, one that for many will recall Daniel Day-Lewis's Oscar-winning portrayal of Christy Brown in My Left Foot . Opposite him Felicity Jones, last seen as Dicken’s mistress in Invisible Woman exudes a quintessentially British quality, a combination of delicate demeanour and an iron will. Supporting roles are also finely handled, particularly by David Thewlis as Stephen’s old professor, Dennis Sciama, another notable in the field of astrophysics and Maxine Peake as Elaine, Stephen’s nurse who eventually becomes his second wife.

But Marsh's film is not just about very good acting. It is a wonderful portrayal of British university life, melded with an albeit typical love story of two youngsters, both smart, both following different fields of learning, but both devoted to each other, with enough staying power to overcome huge odds. Or at least up until their divorce years later. They even mange to have three children.

The pragmatic stuff of how Stephen’s disease unfolds can be viewed with an almost morbid curiosity. His progression from various walking aids to ultimately the hi-tech wheelchair and talking machine which are his trademarks is a real eye-opener into what people with such challenging illnesses have to deal with, and the film portrays it all powerfully well. There are moments when the almost tired trope of geniuses scribbling their formulae manically on blackboards border on the formulaic but even so it’s enlightening to get a tiny glimpse into the overwhelmingly complex world of cosmology.

Perhaps the film could be accused of being too upbeat, given its protagonist’s dire situation. And yet that is probably its heart – as Stephen says, his philosophy is the old chestnut of “where there is life there is hope”. And it is a privilege to have a humanised glimpse into the heart and mind of a modern day genius.

Want more about this film?

Want something different?