Directed by

Jean-Pierre Melville

140 minutes

Rated M

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

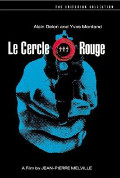

Cercle Rouge, Le

Synopsis: Corey (Alain Delon), just released from prison in Marseille, is en route to Paris. Meanwhile Vogel (Gian Maria Volonté) has just escaped from the custody of Captain Mattei (André Bouvril). By chance their paths cross and together they decide to pull a job. They need the help of a crack marksman, who appears in the form of an alcoholic former policeman named Jansen (Yves Montand).Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Cercle Rouge, the penultimate work by one of cinema’s master stylists, is a perfect marriage between form and content. For this is not just a stylish film it is a film about style, about the Zen of crime and those who follow The Thief’s Way.

This quasi-mystic conception of crime, announced in this film by the putative Buddhistic citation which prefaces the film, is something which Melville developed over time. Not only Le Samourai (1967), which also starred Alain Delon, but his earlier films such as Le Doulos (1961), Bob Le Flambeur (1955), and Jules Dassin's Rififi (1956) all have their traces here. The over-arching mood of these films is not just a resolute dissociation on the part of the characters from the values of bourgeois or petty bourgeois society, but a fatalistic, near ascetic, commitment to the unspoken code of their calling.

In this underworld of Melville’s imagination, of which Le Cercle Rouge is the probably most refined example, it’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game. Ethics and aesthetics are interchangeable. These are men’s men, without attachment to the things of this world (the only one who has here, the nightclub owner Sarti (Paul Crauchet), is compromised). Yves Montand’s role as Jansen is symptomatic of this supra-individualist universe. We initially encounter him a shivering, bedraggled mess in the throes of the DTs in a scene remarkably staged by Melville. He gets a telephone call from Corey requesting his services and in the next scene, he enters a bar for his rendezvous, impeccably attired and implacably self-possessed, a mode from which he never wavers for the rest of the film. Delon’s Corey is the coolest samouri of all, the one who, by example, shows Jansen the true way. The latter’s final scornful remark to his former police associate Mattei (André Bouvril, a comic actor cast here against type) is priceless. If only Leone’s triumvirate of crooks had been this cool (a swarthy Gian Maria Volonté had played the opposite number to a very cool Clint Eastwood in Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, itself a remake of Kurosawa’s samourai film Yojimbo).

Le Cercle Rouge is so determinedly about the form of the crime film and Melville’s particular take on it, that, intentionally or not, he seems relatively unconcerned about details of plot. What happens, simply happens because the narrative requires it. On the other hand the attention to a look or a gesture is meticulous. This is very oriental but it is also very Camusian. Only in the 1950s Parisian existentialist’s world of the absurd that underpins Melville’s work (he was born in 1917, Albert Camus in 1913), could the insignificant be endowed with such importance and so ineluctably pursued (as, for example, in Corey’s final, and utterly futile, act). This re-release of Melville’s film should under no circumstances be missed. Style is dead. Long live le style.

Want more about this film?

Want something different?