Directed by

Martin Scorsese

164 minutes

Rated M

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

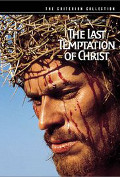

The Last Temptation Of Christ

Despite a disclaimer in the opening titles that it is not The Good Book but Nikos Kazantzakis's 1951 novel which gives Scorsese's film its title, with the exception of the fantasy segment towards its end, Scorsese's film can be regarded as a modern remake, albeit a mercifully shorter one (although still too long), of George Stevens' 1965 Biblical epic, The Greatest Story Ever Told.

On one level The Last Temptation Of Christ, plays like a conventionally reverential account of Jesus's life, complete with all the famous miracles, as realized by some fervid born-again Christian group. Well, except for that fantasy (presumably the last temptation) in Jesus's last hours on the cross during which he imagines living like a normal man, something which I assume was taken from the Kazantzakis novel and which most obviously marks Scorsese’s point of difference from the canonical accounts of the life of the Savior of Mankind.

This embellishment, combined with the overall suggestion of chronic neurosis and eventually serious paranoid delusions understandably created quite a bit of controversy in its day with traditionalists, but the real problem for anyone not invested in the Christian religion is that the film is so jaw-droppingly awful in realization that it regularly comes across as a self-parodizing of the Biblical account. So much so that it may well be regarded as a failed comedy that one laughs at rather than with, a kind of Life of Brian without the jokes.

Scorsese, who as we all know is a master portraitist of urban alienation, shows not the slightest affinity for his material while the film’s script by the director’s regular collaborator, Paul Schrader, is a travesty that borders on the ridiculous, supplying dialogue that makes Jesus and his disciples with their endless blathering about God and Love sound like a cabal of college age Christians at a weekend theological retreat (with one of the attendees regularly bleating about his flock of sheep). And when these lines are spoken by the likes of Scorsese-regular Harvey Keitel as Judas or Harry Dean Stanton as Paul of Tarsus, not to mention David Bowie as Pontius Pilate, the result is simply unfortunate.

Why! There are plenty of actors who could have filled these roles without inviting laughter (the only good news is that Scorsese apparently had enough sense not to rope Robert De Niro into his semi-farce). Much the same inherent lack of credibility goes for Willem Dafoe, who was then at the peak of his career, even if he does admittedly work hard as Scorsese/Schrader’s troubled Messiah whilst getting into the spirit of things, Barbara Hershey (who had starred in Scorsese's only marginally less awful 1972 debut feature, Boxcar Bertha) obligingly disports herself voluptuously as the prostitute Mary Magdalene.

The script, the performances, even the staging (and this is remarkable given Scorsese’s cinematic skills) all conspire to rob the film of a convincing atmosphere at best and any measure of authenticity at worst. It ends with film-stock spooling through the projector gate as if asking us to see the film simply as a story. But when it is told this badly told I'd rather watch the Steven's version.

Want something different?