Directed by

Terence Davies

125 minutes

Rated PG

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

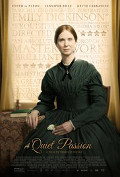

Quiet Passion, A

Synopsis: A portrait of mid-19th century American poet Emily Dickinson (Cynthia Nixon).

No doubt British director Terence Davies wanted to make a film whose form echoed the refined, restrained and constrained life and deeply personal poetry of Emily Dickinson. Arguably he has done so but the result has a counter-productive effect. Meticulously crafted, A Quiet Passion is rather like a object d’art that one feels is too precious to be lived with.

Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886) was brought up in a well-to-do but strictly religious Massachusetts family. Her large output of work, which is now almost universally regarded as being amongst the best of all American poetry, remained largely unknown until the 1950s, only a handful of her poems being published in her lifetime and these altered by their publisher to fit with the grammatical conventions of the time.

Davies’ film is less concerned with the facts of Dickinson’s life than with portraying her change from spirited, independent young woman to sharp-tongued recluse. To this effect he is very selective in what he shows us, most of which - her education, her family life, her unhappy relationships, the backdrop of the Civil War, and so on – are touched on largely tangentially with the bulk of the film being set within the confines of a few rooms of Emily’s home or sometimes breaking for the occasional sortie into the sun-lit garden, these apparently constituting the limits of her world

With a certain proto-feminist vigour we see Emily gamely bristle against the authoritarianism of her sternly patriarchal father (Keith Carradine) and the repressive conventionality of her life but Davies focuses in particular on Dickinson’s disappointments - her best friend, Vryling Buffam (Catherine Bailey) marrying, an unrequited crush on a new pastor (Miles Richardson), her sensitivity to her lack of physical attractiveness and so on – the implication being that the repressiveness of her circumstances and her lack of sexual expression produced an embittered, neurasthenic spinster. As all this unfolds Davies periodically has Dickinson reciting bits of her poetry in voice-over form. She remains the still centre of the film with none of the other characters having a life other than as they relate to Emily (a deficiency most noticeable in the case of her younger sister, Lavinia, played with irrepressible charm by Jennifer Ehle, who despite her evident appeal is also, but inexplicably, suitorless).

Rather oddly, Davies, who also scripted, has Dickinson and her circle do nothing but continuously trade would-be aphorisitic witticisms and ironic barbs like a cénacle of proto-Wildeans in training. Was this the fashion for the day, an expression of the endemic psycho-sexual repressiveness of polite society? It hardly seems likely, at least not in this relentless form. To have heard someone say something banal like “what’s for dinner tonight?” would have been a welcome relief. The endless gnawing at each other and want of a robust day’s work, one feels, would have been enough to drive anyone to the limits of sanity, let alone someone of Dickinson’s heightened sensitivity. Indeed, when late in the film Emily’s brother (Duncan Duff) unkindly reads from an article by her publisher questioning the healthiness of the current avidity among women authors (typified by the Brontës) for hand-wringing emotionalism one can’t help but feel that he’s got a point.

Nixon is fine as Dickinson although given Davies’ approach her acting skill is largely channeled into embodying the film’s title with a certain nervous primness. Fortunately Ehle brings much-needed warmth to proceedings. The rest of the cast are largely stock figures who occasionally emerge from, then retreat back into the shadows..

Is A Quiet Passion what Davies had in mind? Insofar as he has brought us closer to the historical figure but not her work, one suspects not. Still, what he has achieved is something well worth seeing.

Want more about this film?

Want something different?