Directed by

Justin Kurzel

113 minutes

Rated MA

Reviewed by

Chris Thompson

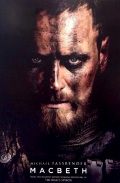

Macbeth (2015)

Synopsis: After distinguishing himself on the field of battle, Macbeth (Michael Fassbender), a Thane of Scotland, receives a prophecy from the weird sisters - a trio of witches - that one day he will become King of Scotland. Consumed by ambition and spurred to action by his wife (Marion Cotilard), Macbeth murders King Duncan (David Thewlis) and takes the throne for himself.

In 1975 I was in fifth form and my English teacher took us on an excursion to see Roman Polanski’s The Tragedy Of Macbeth (1971). Scarred for life! But in a good way. The plays of Shakespeare are fertile ground for adaptation to the big screen and, in addition to Polanski’s visceral and bloody interpretation of the Scottish play, it has been adapted many times before by directors the calibre of Orson Welles (his Macbeth was released in 1948), as Throne of Blood by Akira Kurosawa (1957) and even, right here on the mean streets of Melbourne in Geoffrey Wright’s over-the-top and less-than-successful 2005 outing. Now it’s the turn of another Australian director, Justin Kurzel (Snowtown, 2011) who, to quote the play, is ‘bloody, bold and resolute’ in taking on such a task as only his second feature film.

It can be a tricky thing, responding to screen versions of Shakespeare. We have to remember that, unlike the National Theatre films, these are not ‘captured stage performances’ but cinematic works that release themselves from the limitations of the theatre and embrace the scope of the film medium. Kurzel and cinematographer Adam Arkapaw along with yet another outstanding atmospheric soundtrack from Jed Kurzel, achieve this magnificently, rendering a cold, lonely, isolated Scottish landscape where the appearance of the Weird Sisters in the mist is more beguiling to Macbeth and his comrade, Banquo (Paddy Considine), than frightening.

What often happens with Shakespeare, however, is that in translating his work to the screen, writers and directors can’t resist tinkering with the story. In Michael Hoffman’s 1999 screen version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for instance, a whole ‘dumbshow’ storyline based around Kevin Kline’s character of Bottom was invented. Here, it’s not so much invention as it is adoption of a popular notion that emerged long after the play was written; that the Macbeth’s might have lost a child. This idea is placed front and centre in Kurzel’s version with the film opening on a scene of grief and mourning over their child’s dead body. It certainly adds an emotional punch to the tale, but it also has its downside, offering a kind of psychological backstory that somewhat minimizes the morally-reprehensible actions that Macbeth and his wife take to serve their ambitions. It helps us understand their actions rather than simply being horrified by them. It’s one of the factors that diminishes the culpability of Lady Macbeth and makes her less ruthless than her husband which, whilst strengthening Macbeth’s character, is a disappointment in the way such an iconic character as Lady Macbeth is more commonly portrayed.

There are other revisions to Shakespeare’s work that the purists are likely to regret – no ‘double double toil and trouble’, no Porter scene, and the way in which Birnham Wood comes to Dunsinane, whilst being visually glorious, is not quite as clever as in the original text. Nevertheless, as I said, this isn’t the play, and it’s easy to see why these changes have been made and, if we embrace the notion that this story is more about Macbeth than it is about Lady Macbeth, then there are some chilling new moments that serve this idea well; none more powerful than the brutal manner in which Macbeth personally executes Macduff’s wife and children rather than leaving the task to his henchmen.

The cast, replete with thick Scottish accents, give universally strong performances. Fassbender and Cotillard are, as might be expected, dominating in their respective roles but the standout for me is Sean Harris as Macduff who rounds out a year of great performances (first in '71 and later in Mission: Impossible Rogue Nation with what might be his best yet.

To my mind, Kurzel’s Macbeth falls short on story and character but makes up for the loss in its visual and aural richness. Whilst it doesn’t attain movie-greatness, it certainly earns its place in the pantheon of screen adaptations of the Scottish Play. For me, though, I still have the taste of Polanski’s Macbeth in my mouth, even forty years later.

Want more about this film?

Want something different?