Directed by

John Hillcoat

112 minutes

Rated MA

Reviewed by

Andrew Lee

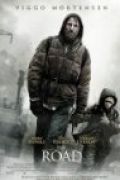

The Road

Synopsis: A harrowing journey taken by a father and young son across a landscape blasted by an unnamed cataclysm, avoiding roaming cannibals, in search of hope.

"The city was mostly burned. No sign of life. Cars in the street caked with ash, everything covered with ash and dust. Fossil tracks in the dried sludge. A corpse in a doorway dried to leather. Grimacing at the day. He pulled the boy closer. Just remember that the things you put into your head are there forever, he said. You might want to think about that."

The Road, Cormac McCarthy

Based on the Pulitzer Prize winner novel by Cormac McCarthy (author of No Country For Old Men), The Road is an uncompromisingly bleak journey in a post-apocalyptic future. The unnamed man (Viggo Mortensen) and his son (Kodi Smit-McPhee) wake to their apparently familiar world of drifting ash, a distant rumble of quaking earth, and the pockmarked road that will take them through a desolate land and occasional dead city to… somewhere.

Heavy in autumnal monotones, where even the highlights are merely burnished brown, the film paints a dark picture of life in a nuclear winter. The man stares out on the landscape, and his eyes are the only thing alive on the screen. Survival is a severe burden, with flashbacks showing the man’s wife (Charlize Theron) struggling to cope with the futility of going on.

The aesthetics of cataclysm are compelling. John Hillcoat has taken the sparse style of his previous film The Proposition and pares it down even more. With a preference for natural shooting, cinematographer, Javier Aguirresarobe, relies on bad weather in abandoned and decayed pockets of Pennsylvania, Louisiana and Oregon to create the apocalyptic landscape. It is matched by a soundscape shifting from subtle atmospherics to an exploding forest fire that shakes your seat, with a subdued score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis.

The man and his son struggle south down the road. There is little dialogue but simple exchanges signify their interior worlds. The man’s occasional narration reflects on their journey, and that he knows “only that the child was his warrant…if the child is not the word of God, God never spoke.” The boy was born into this world years ago, innocent of what came before, and fighting to maintain a thread of hope in the present. He is torn between his father’s justifiable paranoia of others, as they narrowly escape roving cannibals, and his own desire to see the good in someone else.

The core of the film is whether the father is teaching the boy, or whether the boy can save the father from himself. Broader than this is the question of what makes survival bearable, and humanity’s responsibility to its birthplace. Faithful to the tone of its source novel, the film can also be seen as a powerful environmental message. Yet the message is not really creating a powerful level of debate, in comparison to 1965’s The War Game which was banned from television broadcast for 20 years, or 1983’s The Day After which was deemed so traumatizing that broadcasters hosted telephone counseling services for viewers.

That said, the dying world of The Road is still traumatising, depressing, and so single-mindedly, obstinately, bleak that one can understand why suicide is such a temptation for its inhabitants. In this context, the ending may seem conveniently hopeful, but is surely more a sadly ironic and perhaps brief victory of trust over distrust. Many viewers may reasonably enough expect something more than this, to give purpose to the film’s beautifully crafted notes of despair. Yet for those looking for a shining example of the art of cinematic desolation, without much hope of reprieve, this film may be a lasting memory.

Want more about this film?

Want something different?