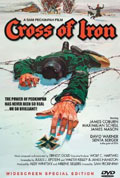

Directed by

Sam Peckinpah

133 minutes

Rated M

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

Cross Of Iron

Sam Peckinpah’s WWII movie is unusual in the annals of American,or indeed, Allied film, in that it takes the perspective of the Germans, with the Russians as the faceless combatants.

Based on a novel by German author, Willi Heinrich, it is set at the end the war as the demoralized Wehrmacht retreats in shambles from the Eastern front hotly pursued by the avenging Russians. The action centres on the maverick German corporal, Steiner (James Coburn), who hates officers and the Nazis but being a good soldier and the man’s man he is, staunchly commands his platoon, who know what a great guy he is, as does his commander, Colonel Brandt (James Mason).Into the mix comes Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell), a wealthy Prussian aristocrat who wants to win the Iron Cross. His only problem is that he’s a coward and bungler and so he must use good men to win it for him.

The focal point of the film is on these contrasting characters and had Peckinpah stuck to this conflict and developed it dramatically the film would have been much stronger. Instead he over-indulges in the action sequences (shot in Yugoslavia) which admittedly for their day are well done with considerable effort expended in making them as realistic and impactful as possible with plenty of his trademark slo-mo effects.

Unfortunately Peckinpah goes right off the rails for a while by romantically involving a convalescing Steiner with an Army nurse (Senta Berger) in a section of the film which is not only entirely gratuitous but also poorly realized (perhaps explained by the fact that the film ran into budgetary problems) and again later in proceedings by having the platoon stumble across a squad of half-naked female Russian soldiers.

Much of this sounds like Peckinpah machismo run amok but Cross Of Iron is not only an anti-war film with considerable punch, portraying the ordinary soldier’s experience in combat it also explores various kinds of male love, from outright homosexuality to the more polymorphic relations between the men of Steiner’s platoon.

Although the film ends with a deeply cynical quote from Brecht on man’s seemingly compulsive need to be the aggressor, it is Steiner’s words to a young Russian that he has saved and is about to set free that sums of the essence of the story: “It’s all an accident, an accident of hands. Mine, others, all without mind, from one extreme to another, but neither works nor will ever. Yet we stand here in the middle of no man’s land”

The film bombed in America where it was cut to 119 minutes, but it did well in Europe, particularly in Germany and although now well superseded deserves some recognition for pointing the way to subsequent war films such as Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) and Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line (1999).

Want something different?