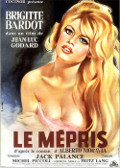

France/Italy 1963

Directed by

Jean-Luc Godard

103 minutes

Rated MA

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

Contempt

Although Jean-Luc Godard's film is first and foremost an essay in cinematic style it also works as a portrait of the vanity of man (as opposed to woman). “Man” here is represented in two forms as Michel Piccoli’s screenwriter, Paul Javal, and Jack Palance’s film producer, Jerry Prokosh. “Woman” is Brigitte Bardot’s Camille, the beautiful young wife of Paul. Probably truer of the times than today she is a property more than a person and her beauty becomes a commodity that the two men each in their own ways crudely desire. The film’s title refers to Camille’s feeling for Paul as he does nothing to protect her or assert himself before Jerry’s rapacious advances.

Of course, being Godard this is no straightforward story of the disintegration of a relationship and from the opening scene showing a camera (operated by the film’s cinematographer Raoul Coutard) tracking one of the film’s characters as she walks towards us as Godard voices the credits, Contempt is also a running commentary on film making as art and commerce, not a little because of the casting of legendary film director, Fritz Lang.

The story concerns Prokosh’s hiring of Paul to rewrite the script that Lang is using to make a version of the Odyssey. Paul needs/wants the money in order to keep his lifestyle with Camille and doesn’t believe that Camille is more interested in their relationship than money. The production goes to Capri to seek inspiration but Camille grows increasingly disaffected and Paul is powerless to do stop the inevitable.

Coutard’s widescreen cinematography is superb (in typical form Godard has Lang crack that it is a form only suitable for snakes and funerals) and the art direction of the interiors and the dramatic exteriors of Capri form a marvellously stark backdrop the battle between Paul and Camille as

Then there’s Godard’s portrayal of Bardot as both object and subject. The first aspect is essentialized in the camera’s lingering over her svelte naked body which is not so much exploitative of Bardot as a quotation of the classic pin-up representation of female beauty (Godard was still at the time married to Anna Karina who had filled a similar role in Godard’s classic New Wave films and one wonders why she wasn’t cast here). This is the Camille that Paul and Jerry see (the opening red-tinted section in which the naked Bardot teases Paul about her body was apparently added by Godard after the completion of filming to indulge the film’s producers). But Godard also makes Camille the epicentre of the film and it is not too much to say that it is her perspective on Paul and Jerry that we see. Bardot rises empathetically to the occasion in what is probably her finest screen appearance (and an interesting presage of her choices in real life).

Much as Godard took the Hollywood gangster movie and reworked it in Breathless with Contempt he takes what in Hollywood would have been an over-heated melodrama (it was adapted from Alberto Moravia's novel "Il Disprezzo") and turns it into a elegantly melancholy essay on the illusions of life.

Want something different?