Directed by

Terrence Malick

94 minutes

Rated PG

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

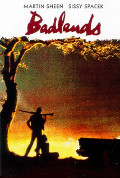

Badlands

Synopsis: It's South Dakota, 1959. Kit (Martin Sheen) and Holly (Sissy Spacek) fall in love, he kills her Dad (Warren Oates) and they head for the Badlands of Montana.

The general understanding that Badlands is about a young couple on a killing spree across America is a serious misrepresentation, for this is no edge-of-your-seat action film. It is rather about a misbegotten and ill-fated romance, a time-honoured dance between Eros and Thanatos. The murders are collateral damage of that mythic story. Malick's film is more Bonnie And Clyde (1967) than Natural Born Killers (1994).

Although the story is based on real life events, Kit and Holly are typical outsider figures, he by design, she by association. The use of a monotone voice-over narration by Holly (superbly played by Spacek) serves well to distance us from the actuality of things, which here occur in a trance-like suspension, seen through Holly's wide and vacant eyes. This distantiation pleased the critics in some quarters, giving the film cult status and earning it a 2002 re-release.

Malick is unquestionably a master craftsman and this is a visually stylish film which uses music in a way that David Lynch would pick up on in Blue Velvet (1986). Malick's directorial peers, Coppola and Scorsese, have been enormously successful in romanticizing murder and making it the objject of vicarious viewer pleasure, re-fashioning the Western in the guise of the crime movie and exploiting the mythos of the gun-toting hero to elevate gangsterism to the level of a noble profession. Particularly with Scorsese, the question arises of what comes first, the gangster or the movie.

Taking this process even further Malick poeticises his subject beyond all recognition. One cannot smell Kit's garbage truck, his victims die compliantly with only a small red stain to mark their injury, the young fugitives cross hundreds of miles of barren scrubland without a flat tire or an empty petrol tank. And through it all, Kit's good looks mean that his mental and moral dissociation comes across as a charming laconicism. Unfortunately, sometimes this is so overplayed that the film almost appears to be a black comedy, the sort of thing that Jim Jarmusch would do. But then Jarmusch would never have such lamentable taste.

This opposition between form and content divorces Badlands from the real world on which it is based and thereby interrupts emotional engagement. Which might be just what Malick wanted to do. If so whether he was right or wrong in his approach to that outcome is a question for debate.

Want something different?