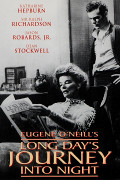

Directed by

Sidney Lumet

174 minutes

Rated PG

Reviewed by

Bernard Hemingway

Long Day’s Journey Into Night

I like a dysfunctional family drama as much, if not more, than the next man but Sidney Lumet’s transposition of Eugene O'Neill's autobiographical stage play Long Day’s Journey into Night is a musty, tiresomely reiterative affair.

Set on a summer’s day in 1912 at the Connecticut summer home of the Tyrones, father (Ralph Richardson), an alcoholic narcissist and skinflint, his “dope fiend” wife Mary (Katharine Hepburn) and their adult sons Edmund (Dean Stockwell), a neurasthenic consumptive and Jamie (Jason Robards Jr.) a wastrel with his father’s fondness for the bottle, spend the day and night alternately excoriating and commiserating each other.

Despite the fact that the play is regarded as a classic of 20th century theatre and in its days the film was rapturously received it is difficult to why Lumet gives us nearly three hours of hand-wringing misery. Some pruning of the text may not have improved the film but at least it wouldn’t have droned on for so long,

Departing little from its stage parameters the drama is set largely in the Tyrone’s sitting room a closeness which is exacerbated by cinematographer Boris Kauffman’s fondness for zooms, extreme close-ups and circumambulatory camera-work none of which adds anything to the experience. Quite the reverse in fact. This is surprising because Lumet had notable success in an even more confined space with 12 Angry Men (1957) and various prior stage-to-television adaptations

The cast is an ill-assorted lot with no apparent family resemblance between the four players (there is one small scene with a fifth character, a housemaid). Hepburn, who looks like a wreck in close-up seems to have just attended a refresher course at the Norma Desmond School of Over-Acting, and in the film’s most dominating performance chews the scenery to such an extent that it is a relief when she is off-screen. Showing much more reserve Richardson carries on like a vaudevillean Shakespearean from the Old Country which, indeed, he is supposed to be but comes across more as W.C. Fields at home than a former matinee idol. Robards, who had played the part on Broadway and who is too old for the role, makes Jamie into some kind of Paul Newman rebel and Stockwell, an obvious stand-in for O’Neill himself, is feyly sensitive.

No doubt the individual qualities of these characters were there to be embodied by the actors but instead of genuine connections between them Lumet gives us relentless histrionics that at times veer into the self-parodic.

FYI: For much better renditions of related material see Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and Death of a Salesman (1985).

Want something different?